District 8 Book Club - Courage to Dissent

We need shared resources to collectively provide for those that are otherwise struggling in some form or another; we call this government.

INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK CLUB

I read a lot. Or, I try to read a lot. I generally have 3 or 4 categories that I read going at any one time. The first is just the general news kind of stuff that I read every morning – the New York Times (and Wordle), the Atlantic, the Athletic, and Reddit are how I spend every morning with a cup of coffee when I first wake up. Then, throughout the day, I have my work-related stuff that I read (recall, I am a law professor and lawyer in my day job) – student materials, cases, scholarship, white papers, legislation. Then, at night as I’m going to bed and for recreation, I read fiction – some more frivolous than others.

But I have a fourth kind of material that I read, too. I’ll call it “professional development.” It might be a book where I’m trying to learn about a specific thing (like systems thinking frameworks), or a book where I’m trying to understand the world a little better (like sustainability in the fashion industry) or just trying for a bit of the ol’ self-improvement (like trying to better understand systemic racism). This “Book Club” will be some of the books in this fourth category that I think are particularly relevant to life in public service.

“Book Club” might be a bit strong – there is no one else reading these books with me, unless you – dear reader – would like to follow along. For the most part, these will be my thoughts (i.e., a book report), but I will try to post ahead of time what the next book will be so you can read it too, if you want. I will also turn on commenting for these posts so if you want to discuss the book, so please feel free to post your thoughts. But be warned that I will heavily moderate these discussions, so please keep it relevant and on-topic.

I do not receive any affiliate credit for any of the links below, the links are just there to make finding the books a little easier.

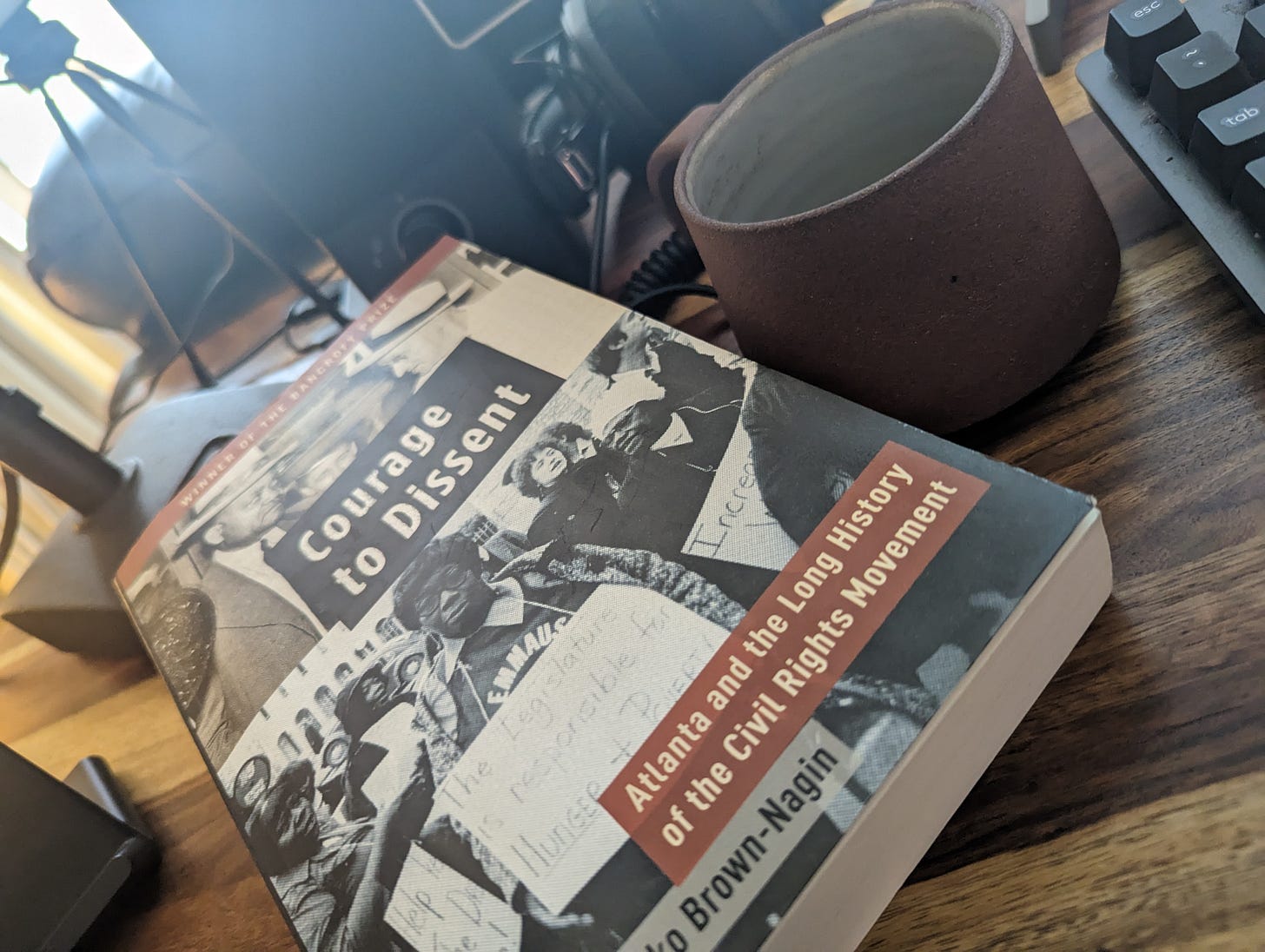

CURRENT BOOK: COURAGE TO DISSENT – TAMIKO BROWN-NAGIN

Being in public service is new to me, but being in community activism is not.

As you’ve seen on my bio, I have long been an active leader in a variety of communities. I don’t think that bio necessarily does my community work the justice it deserves – others would probably highlight much more that I’ve done – but let’s just call it Midwest humility. Frankly, it’s all been very “learn as you go” so it never really felt as intentional as it has since I’ve moved to Madison in 2007 (over 15 years ago now).

Prior to Madison, though, I was a team captain on numerous sports ball teams, I led numerous work and academic project teams, and I led social groups. I was relatively uninterested in politics until I moved to Madison. Indeed, I had only voted on exactly one occasion prior to moving to Madison at age 32. Not because I wasn’t interested in civic engagement but because I was uninterested in what those leaders were saying – it never felt particularly relevant or impactful to me because it wasn’t my day-to-day life.

Reaganonomics, censorship, homelessness, even abortion and racism – at the level that my friends and I engaged with them – didn’t feel terribly related to the way in which our elected officials talked about them. My parents were never political people, either (although my grandfather was an elected official before I was born; when I knew him, he owned drive-through liquor stores) – or, if they were, they didn’t really share much of their politics with me. This was back in the day when adults didn’t discuss such things with their kids and it was impolite to discuss politics at the dinner table. Thus, while those discussions may have actually been relevant, as a young punk I didn’t see it.

I did, however, see friends that were denied access to education on the basis of their skin color. I did, however, know of friends and their partners who found themselves needing healthcare services and unable to afford it. I did, however, encounter numerous kids at the coffee shops at 2am who were there simply because they had nowhere else to go. My response wasn’t to run to my elected official and demand legislative reform. My response wasn’t to turn to a lawyer and sue.

My response was to speak truth to power where others couldn’t. My response was to connect my friends to other friends who could get them the care they needed. My response was to invite those kids at the coffee shop to crash on my floor. These were things that I could do that actually solved problems but weren’t particularly connected to whatever the national discussion was that was going nowhere. Did I solve “big” national problems? No. But it did help the people that needed it at the time they needed it.

Of course, whether someone does or doesn’t get healthcare or shelter for the evening shouldn’t depend on whether they know Jeff or not. So, we need shared resources to collectively provide for those that are otherwise struggling in some form or another; we call this government. We all pool our money together (taxes) and we pay for things (like bus systems) so that people who need help (they don’t have a car) can survive. Our elected officials, our representatives, are the stewards of that public resource and set the rules for how those resources get shared (we call these laws or ordinances).

In Atlanta in the late-50s, almost none of the public resources were being shared with black people. Their representatives had put laws in place that specifically prevented a group of people (black people in this case) from accessing the public resources. So, groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sued the City of Atlanta (amongst others) for access. They sued over access to golf courses, swimming pools, restaurants, buses, and education just to name a few. The courts of Atlanta, Georgia, and the United States all agreed with the NAACP, the laws segregating black from white were removed from the books, and there was much rejoicing.

Well, they rejoiced when they weren’t being lynched for daring to use the public resource. They rejoiced when they weren’t being arrested on frivolous charges for daring to use the public resource. They rejoiced when they weren’t being locked out of schools, bused all over the county, or denied promotions. They rejoiced when they weren’t being denied home loans for mortgages in white communities.

Legalistic solutions can only go so far. The book points out that desegregation is great as a theory and we can have laws that mandate that blacks be allowed to attend public schools and otherwise have equal access to shared resources. But we can’t legislate every single decision that needs to be made. In my lawyer world I often tell people: “You’re only as right as you can afford to be.” Even if the law allows you to attend the school, if the cop shows up and arrests you for trespassing anyway, you only get out of jail if you can afford the lawyer (or a public defender, to the extent one is even available, has the time and capacity to help for free – but even that person is paid by the very “criminal justice” systems that put you in jail in the first place, and we go round and round).

And this, of course, is the central tension of the book: how to accomplish both things at the same time – the grand legal vision and the practical access to shared resources. There is an inherent tension between the legal formalism of the court systems and the pragmatism of just trying to get an education (or swim or eat or play golf) without being arrested. The law can allow you to go to a school, but if in passing the law racial tensions are inflamed, then it doesn’t really matter what the law says when you are a poor, black child sitting in jail on a trespassing charge (or worse) because a white cop is mad.

But the book’s clarion call is without response: how do you balance all of the interests involved in a way that advances a movement (in this case, civil rights). For as impactful and important as the NAACP and others’ lawyers were, the change is only so good as the people who implement it. Or, stated differently, a movement needs lawyers to change the laws, but also to bring together people to want to implement the change. One cannot be useful without the other. In the context of the book, if the law forces desegregation but the community doesn’t see the value in the change, then how effective, really, is the change?

Obviously, not every member of the community has the same interests. At is simplest we can just look at the reaction of many whites in Atlanta in the face desegregation – a retrenchment or even increase in hostilities against blacks. The book makes the case that for many upper-class or even middle-class blacks in Atlanta in the 60’s the formalism of court solutions could be tolerated because they didn’t feel the impact of segregation in the same way as the poor. But, for poor blacks in Atlanta, they felt the intolerance to desegregation in a very different way. Some felt that maybe desegregation wasn’t so great so long as they could get access to sufficient resources.

Or, as stated more eloquently by Dr. Benjamin Mays, President of Morehouse College, mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr, and Chair of the Atlanta Board of Education:

“I have great pride in Negro banks, Negro insurance companies, Negro churches, the Negro press, Negro colleges, and every worthwhile institution that Negroes run and control. … I refuse to be swept off my feet by the glamour of a desegregated society. … Nothing I say here must be interpreted to mean that I believe in a segregated society or segregated education. … [But,] I think you can have a quality education given equal facilities, equal library, equal buildings, and teachers with the same qualifications.”

Pg. 422-423

For poor blacks and students, a focus on community engagement to change attitudes needed to come before (or at least alongside) the legal challenges. This “community engagement” took many forms: from attempts to negotiate a slow, step-wise approach to integration with white leaders to radical lunch counter sit-ins. But the slow approach was too slow, and the radical approach too radical, for those that insisted on the more legal, court-centric approach.

As the book points out: just because desegregation is “better” for “blacks” generally, doesn’t mean that the “individual” can’t get a quality education in a separate, but equal school free of white hostility during the learning process. Shared resources and quality education are both worthwhile goals, but the legal formalism can’t be allowed to prevent a kid from getting a good education if in doing so their day-to-day life is so miserable they aren’t learning anything. The book spends multiple chapters pointing out how the NAACP, with its focus on legal formalism, had lost touch with the pragmatism of living day-to-day life and got too far out in front of the community. How can the NAACP decide who or what to sue about if they don’t fully understand the needs of those they represent?

We can’t achieve the end goal (desegregated quality education for everyone) until we recognize that each constituent has their own specific needs to be met and simply relying on legal formalism is insufficient to meet those needs. The legal wins don’t mean anything if there isn’t community buy-in. Or, stated differently:

“… the connection to community increases the likelihood of accountability. Rather than first identifying a goal and then rallying the community to the cause, the movement lawyer sets an agenda and determines goals only through collaboration with local communities and organizations.”

Pg. 442

The book is written by an academic for a lawyer audience. So, it is a very dense read. It took me the better part of 18 months to read through all 442 pages. It heavily features civil rights lawyers; Thurgood Marshall, Constance Baker-Motley, AT Walden, and Len Holt are all highlighted (amongst many others). Together they showcase the different roles that lawyers play from litigator to community organizer: world class formalism and the pioneers of modern pragmatism. Changing the law and changing minds.

NEXT BOOK: HOW THE OTHER HALF BANKS – MEHRSA BARADARAN

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/25366656-how-the-other-half-banks?ref=nav_sb_ss_1_24

Bookshop.org:

https://bookshop.org/p/books/how-the-other-half-banks-exclusion-exploitation-and-the-threat-to-democracy-mehrsa-baradaran/6708667?ean=9780674983960

Blurb: The United States has two separate banking systems today–one serving the well-to-do and another exploiting everyone else. How the Other Half Banks contributes to the growing conversation on American inequality by highlighting one of its prime causes: unequal credit. Mehrsa Baradaran examines how a significant portion of the population, deserted by banks, is forced to wander through a Wild West of payday lenders and check-cashing services to cover emergency expenses and pay for necessities–all thanks to deregulation that began in the 1970s and continues decades later.